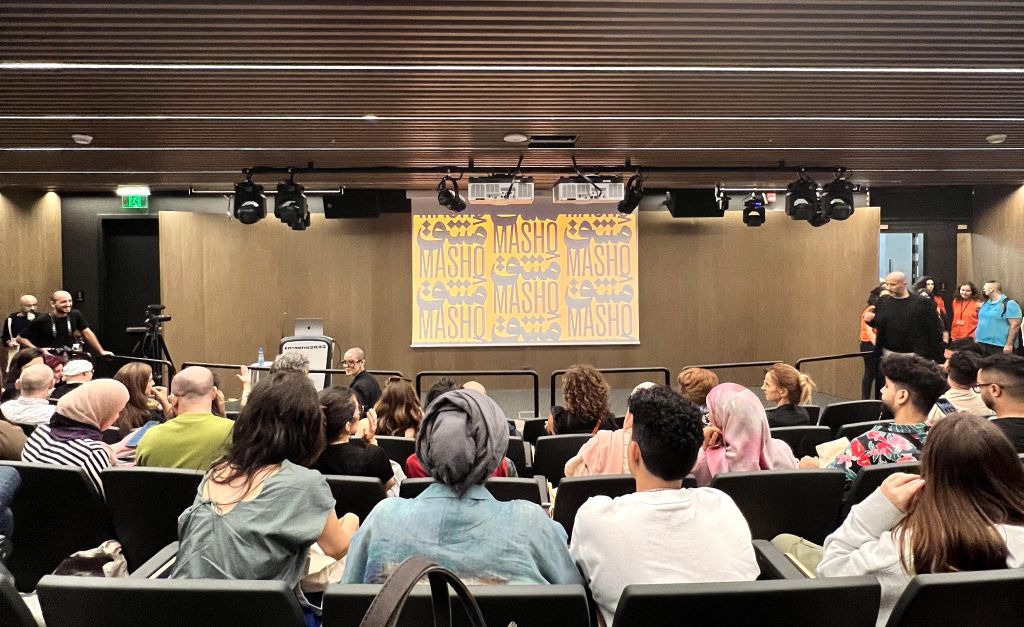

An Encounter with Arabic Type

Mashq Conference, October 2022

By Youmna Habbouche

My colleagues and I recently witnessed, at the American University of Beirut, professionals, scholars, and students coming together for a day and a half. They explored historical developments, research material, technology updates, and emerging trends in the field of Arabic typography, type design, lettering, and regional visual communication in particular. The event was inspiring, to say the least.

The seminar kicked off with an introduction from dean Alan Shehadeh of the Maroun Semaan Faculty of Engineering and Architecture. It is the venue for the design program and the event, putting things in perspective. Yara Khoury, one of the organizers, who also happens to be my teacher back at the university, explained the need for organizing this event. Leila Musfy, one of the first design professors at AUB, showed us via an avant-garde presentation with cute cats, how it all began.

We were then moved by a serenade from the master calligrapher. Moreover, we also heard from the art critic, poet, writer, and researcher—Samir el Sayegh. He talked about how calligraphers and designers work together to make Arabic letters that can be used in print, as well as how they can be updated.

Throughout the conference, El Sayegh and many other speakers expressed their disappointment at seeing the calligrapher’s role clearly ending in improving design matters. Since Arabic letter printing spread to the East, calligraphers haven’t done much to improve letter design. Instead, they focused on calligraphy as an independent art, and traditional lettering became a free form rather than a modernized discipline. It is true that we have not seen any new forms of Naskh or Nastaliq exploration.

That first day ended with the opening of two exhibitions: a retrospect of the last edition of the 100 Best Arabic Posters Competition, as well as a focus on the Granshan Give Voice to Type. Both were winning entries in the Arabic text and display typefaces.

As designers from this day and age, the overall message of this exhibit clearly tells us that our identity remains quite fluid: while some of us still look to the West as a design reference and inspiration, utilizing the common language as an aesthetic element rather than a communication one, others try to push boundaries and introduce new visual expressions.

Day two started out with a work presentation from Salem el Qassimi and an insider’s view of the process behind the different activities of his UAE initiative Fikra: a studio for professional commissions, design residencies, exhibitions, and talks. It’s quite inspiring to see the stretching of culture in contemporary design practice, especially in the GCC region, where setups for research and experimentation are becoming the norm, thus creating a hub for emerging new visual languages.

“الخط يكتب. الحرف يطبع.”

Calligraphy is handwritten, Type is printed

Next up was guru Kameel Hawa, founder of Al Mohtaraf Design House, walking us through his own experience and visual experimentations, from sketches to physical sculptures. Hawa spoke slowly and carefully relayed his thoughts and recommendations to the rising generation of designers, almost like a memoire. His work embodies his own words: “You need three things to be a great designer: you should be able to carry your heritage, be present in your time, and be true to your authentic artistic self”.

Research, connections, experimentations, lettering, and more were the subjects of Dr. Huda Smitshuijzen AbiFarès, founder and director of the Khatt Foundation. She has been building our regional legacy with books and curated publications specializing in Arabic and multilingual typography. I was glad to find that this collection included some new books I hadn’t seen before, like the Dia Al-Azzawi retrospective and the new edition of the Arabic Typography Sourcebook, which was one of the first design books I bought.

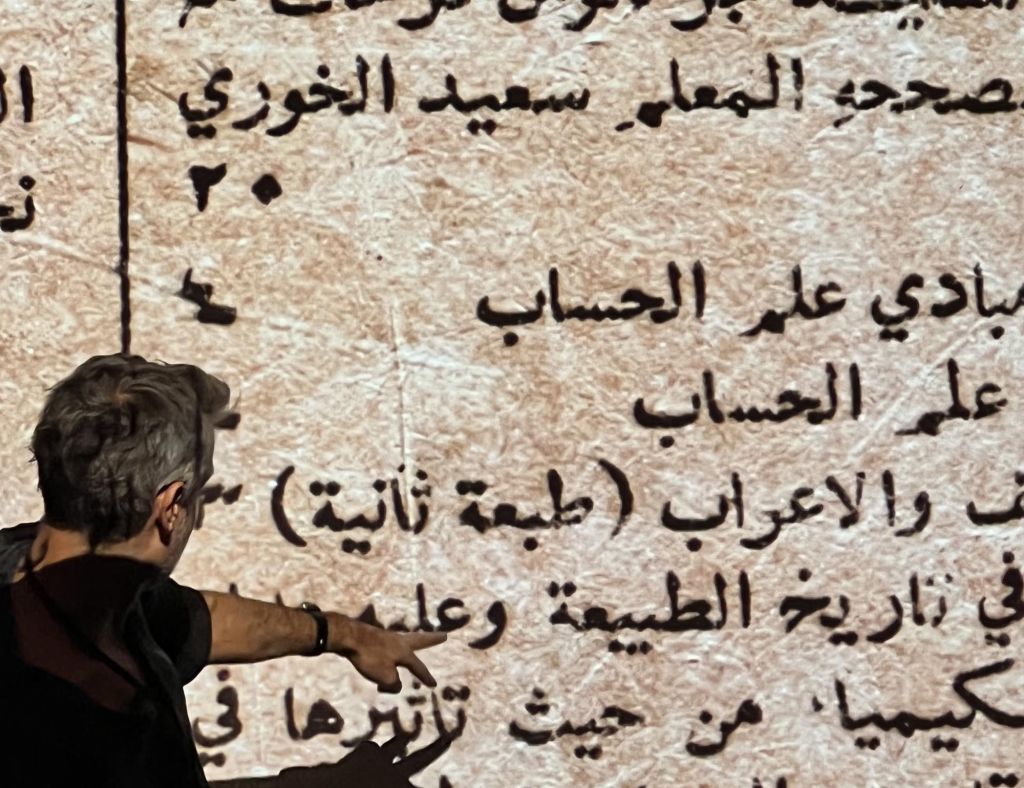

We then dove, with Onur Yazicigli (is_type), into examining Ottoman Naskh typefaces as a trade commodity and how those were exported, recreated, and published beyond Constantinople, in Europe but also in Beirut and Cairo—centers of Arabic publishing in the late nineteenth century. There was so much passion in Yazicigli’s research work and his historical analysis, backed up with old photos of the type makers as well as documents and sample prints from the Ottoman Imperial Archives and Beirut’s ancient Imprimerie Catholique. We looked at dots on isolated letters (ن), superimposed typefaces, and retraced some findings back to Twitter discoveries. Needless to say, I have a soft spot for links between Beirut and Istanbul, but this was beyond fascinating.

Bahia Shehab moved quickly into an interesting timeline of the Arabic script, from calligraphy to design and art. Artists, illustrators, designers, typefaces, techniques, and so much more in only a few minutes, with a logic that was so personal to her, it actually made it even more captivating. It was like a quick espresso shot, leaving you energized and ready for more!

Naïma Ben Ayed, who like many other designers grew up with both Latin and Arabic, teamed up with Khajag Apelian as part of the School of Commons. They put together their experiences as designers and educators to reflect on the status quo of Arabic-type design pedagogy. Moreover, they shared ways to open and expand it in the near future. She walked us through the process designed so far. It was really impressive to see how easy it was to learn Arabic lettering in cluster-fast workshops, which used a different method of teaching.

Lara Assouad told her story in Arabic type in four acts: a child growing up and rebelling against a language that meant belonging; a design student focused on the aesthetic of shapes rather than words; a new professional being asked to work with the language; and an esteemed graphic and type designer. Assouad’s path is exemplary in that she juggles the aspirations of a skilled designer with cultural work that goes beyond commercial needs, delving into the physicality and symbolism of the Arabic alphabet, its modularity, and its rhythm beyond its function as a language and cultural signifier.

In (borderline) dark humor, Nisrine Sarkis relayed her/our frustration with the client being always king and the reality of designing for commercial use. She meticulously kept all her sketches and initial propositions for projects she had worked on, and showed the beautiful work she had suggested in comparison to the customer’s final choice: relatable and hilarious! But having made that point, she also spoke about the constant struggle of being asked to make Arabic type look Western, instead of modern in its own characteristics.

In contrast, we got to observe Jana Traboulsi, being her spontaneous self and showing bits and pieces of her path from drawings to lettering, posters to publications. It was fascinating to see how Jana’s work challenges all the norms of perfection in a world obsessed with perfection; it makes it perfectly imperfect and appealing in that sense — pure and almost like a reverie.

Building ligatures and openness between cultures via type design was a major challenge for Veronika Burian from Type Together. She explains how the process of creating a typeface with multiple scripts is important, and then, so eloquently, she concludes:

“Type itself might not change the world, but it could help us communicate better, transport values and understand each other so much better.”

Hatem Imam from Studio Safar raised questions about graphic design’s resistance to a solid definition. “Problem solvers, they call us,” reads one of his slides. What are we? Why isn’t our role clearly stated as cultural practitioners? Designers impact our choices as consumers in terms of political stands, cultural belonging, etc. It makes us ask ourselves: Why do we shy away from associating ourselves with collective impact and often minimize our roles to small artboards and color palettes?

At Misfits, our community of designers is constantly challenged by changing this narrative. Clients often don’t understand this is a real struggle; they can help us grow the boundaries of local culture. Unfortunately, reality has it that attracting business always comes before the wish of creating change; at least for commercial businesses.

Our junior designers Najat Kibbi and Robin Khalil, who I was surrounded with throughout the talks, left the venue fully inspired, and full of pride for belonging to this circle of Lebanese and regional designers who do such beautiful work.

Personally, I left with an impression of belonging to a generation of designers and researchers who have unwillingly lived or are living away from home. Our visual boundaries got blurred. Local traditions and modern Western influences were forced to be put together and were sometimes pushed apart. We danced our way through years of professional and cultural experimentations and findings.

We have reappropriated a language and a script, tamed it, worked passionately around it, and put effort into translating how we visually read and perceive it, sometimes with an outsider’s view of our own culture – almost in the eyes of people who observe it from afar, almost as strangers.

NB: There were also 2 lectures by Emile Menhem and Georg Seifert which we had to unfortunately skip 🙂

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you. https://accounts.binance.com/fr-AF/register-person?ref=JHQQKNKN

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good. https://accounts.binance.com/zh-TC/register?ref=VDVEQ78S

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks! https://www.binance.com/zh-TC/register?ref=VDVEQ78S

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

Ищите в гугле

Thanks to share

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

‘and/**/extractvalue(1,concat(char(126),md5(1470295422)))and’

‘”\(

‘and’s’=’s

‘and(select*from(select+sleep(4))a/**/union/**/select+1)=’

‘and(select+1)>0waitfor/**/delay’0:0:0

‘and/**/extractvalue(1,concat(char(126),md5(1789103496)))and’

‘and(select’1’from/**/cast(md5(1427436643)as/**/int))>’0

convert(int,sys.fn_sqlvarbasetostr(HashBytes(‘MD5′,’1347513011’)))

鎈'”\(

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article. https://accounts.binance.com/cs/register?ref=S5H7X3LP

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

They’re at the forefront of international pharmaceutical innovations.

buy generic lisinopril pills

A trailblazer in international pharmacy practices.

The staff provides excellent advice on over-the-counter choices.

where buy cytotec without a prescription

Cautions.

I trust them with all my medication needs.

gabapentin purpura

The staff ensures a seamless experience every time.

A model pharmacy in terms of service and care.

where can i buy generic lisinopril pill

Their worldwide delivery system is impeccable.

Efficient, effective, and always eager to assist.

where to get cipro no prescription

The team embodies patience and expertise.

alo789 dang nh?p: alo789 dang nh?p – dang nh?p alo789

https://interpharmonline.shop/# canadian pharmacy cheap

pharmacy in canada

IndiaMedFast: India Med Fast – india pharmacy without prescription

canadian pharmacy king: Cheapest online pharmacy – canadian pharmacy no scripts

https://interpharmonline.com/# canadian pharmacy online ship to usa

canadian drug prices

canadian pharmacy 365 highest rated canadian online pharmacy reliable canadian pharmacy reviews

http://interpharmonline.com/# my canadian pharmacy rx

legitimate canadian pharmacy online: InterPharmOnline – canadian drugstore online

cheapest online pharmacy india: online medicine shopping in india – cheapest online pharmacy india

https://indiamedfast.com/# IndiaMedFast.com

canadian pharmacy ltd

India Med Fast: cheapest online pharmacy india – buying prescription drugs from india

medication canadian pharmacy: Certified International Pharmacy Online – best online canadian pharmacy

https://indiamedfast.com/# online pharmacy india

canadian pharmacy india

https://indiamedfast.shop/# IndiaMedFast.com

pharmacy com canada: online canadian pharmacy no prescription – canada discount pharmacy

http://interpharmonline.com/# pharmacy canadian superstore

the canadian drugstore

Mexican Pharm Inter: mexican drug stores online – reliable mexican pharmacies

http://mexicanpharminter.com/# mexican pharmacy online store

online medicine shopping in india online medicine shopping in india lowest prescription prices online india

cheapest online pharmacy india: India Med Fast – IndiaMedFast

https://interpharmonline.shop/# canada drugstore pharmacy rx

77 canadian pharmacy

https://indiamedfast.shop/# india online pharmacy store

my canadian pharmacy: InterPharmOnline.com – canadian pharmacy drugs online

online canadian pharmacy: fda approved canadian online pharmacies – pharmacy canadian

https://indiamedfast.shop/# online medicine shopping in india

ed drugs online from canada

buy drugs from canada legitimate canadian pharmacies online precription drugs from canada

https://mexicanpharminter.com/# mexican pharmacy online store

canadian online drugs: fda approved canadian online pharmacies – best canadian online pharmacy

http://interpharmonline.com/# medication canadian pharmacy

best online canadian pharmacy

https://interpharmonline.shop/# reputable canadian pharmacy

https://kamagrakopen.pro/# KamagraKopen.pro

Generic 100mg Easy buy generic 100mg viagra online Generic 100mg Easy

http://generic100mgeasy.com/# buy generic 100mg viagra online

cialis without a doctor prescription: TadalafilEasyBuy.com – Tadalafil Easy Buy

kamagra gel kopen: kamagra pillen kopen – Kamagra Kopen

https://kamagrakopen.pro/# Kamagra

https://tadalafileasybuy.shop/# cialis without a doctor prescription

buy generic 100mg viagra online: Generic 100mg Easy – Generic100mgEasy

Kamagra: kamagra pillen kopen – Kamagra Kopen Online

http://tadalafileasybuy.com/# п»їcialis generic

http://tadalafileasybuy.com/# TadalafilEasyBuy.com

Kamagra Kopen: kamagra jelly kopen – kamagra kopen nederland

https://tadalafileasybuy.shop/# TadalafilEasyBuy.com

kamagra gel kopen: Kamagra Kopen – Officiele Kamagra van Nederland

http://generic100mgeasy.com/# over the counter sildenafil

kamagra gel kopen kamagra jelly kopen Kamagra

TadalafilEasyBuy.com: Cialis 20mg price – Tadalafil Easy Buy

kamagra 100mg kopen: KamagraKopen.pro – Kamagra Kopen

http://generic100mgeasy.com/# Generic 100mg Easy

https://tadalafileasybuy.com/# TadalafilEasyBuy.com

buy generic 100mg viagra online: Generic100mgEasy – Cheap Viagra 100mg

cialis without a doctor prescription: Generic Cialis price – cialis without a doctor prescription

https://tadalafileasybuy.com/# Buy Cialis online

TadalafilEasyBuy.com TadalafilEasyBuy.com TadalafilEasyBuy.com

https://kamagrakopen.pro/# kamagra pillen kopen

TadalafilEasyBuy.com: cialis for sale – Tadalafil price

Tadalafil Easy Buy: Buy Tadalafil 20mg – buy cialis pill

https://tadalafileasybuy.com/# Tadalafil Easy Buy

kamagra kopen nederland: Kamagra Kopen Online – KamagraKopen.pro

Generic100mgEasy: buy generic 100mg viagra online – buy generic 100mg viagra online

Kamagra Kopen Online kamagra 100mg kopen Kamagra Kopen Online

https://kamagrakopen.pro/# Kamagra Kopen

TadalafilEasyBuy.com: cialis without a doctor prescription – buy cialis pill

https://tadalafileasybuy.shop/# Tadalafil Easy Buy

https://tadalafileasybuy.com/# Buy Tadalafil 10mg

Officiele Kamagra van Nederland: KamagraKopen.pro – kamagra kopen nederland

http://tadalafileasybuy.com/# Tadalafil Easy Buy

kamagra 100mg kopen kamagra pillen kopen kamagra gel kopen

https://kamagrakopen.pro/# KamagraKopen.pro

kamagra gel kopen: Kamagra Kopen – Kamagra Kopen Online

Kamagra Kopen: Kamagra Kopen Online – kamagra jelly kopen

https://kamagrakopen.pro/# Kamagra Kopen Online

TadalafilEasyBuy.com: Tadalafil Easy Buy – Tadalafil Easy Buy

https://kamagrakopen.pro/# kamagra 100mg kopen

kamagra jelly kopen Kamagra Kopen Online Officiele Kamagra van Nederland

пинап казино – пинап казино

пин ап: https://pinupkz.life/

пин ап зеркало – пин ап казино зеркало

pinup 2025 – пин ап казино

пин ап казино – пин ап

пин ап казино официальный сайт: https://pinupkz.life/

пин ап казино зеркало: https://pinupkz.life/

пин ап зеркало – пин ап казино зеркало

pinup 2025 – пин ап зеркало

Tadalafil Easy Buy cialis without a doctor prescription TadalafilEasyBuy.com

пин ап вход – пин ап вход

пин ап казино официальный сайт – пин ап казино официальный сайт

Generic100mgEasy Generic100mgEasy Buy Viagra online cheap

пин ап зеркало – пин ап зеркало

пин ап – пин ап казино официальный сайт

пин ап казино официальный сайт – пин ап зеркало

пин ап казино – пин ап казино официальный сайт

Apotheek Max: Beste online drogist – Apotheek online bestellen

http://apotekonlinerecept.com/# apotek online recept

Kamagra online bestellen: Kamagra kaufen – Kamagra kaufen ohne Rezept

online apotheek Online apotheek Nederland zonder recept Online apotheek Nederland zonder recept

https://apotheekmax.shop/# de online drogist kortingscode

apotek pa nett: Apoteket online – apotek online recept

online apotheek: Online apotheek Nederland zonder recept – de online drogist kortingscode

http://apotheekmax.com/# Online apotheek Nederland zonder recept

https://apotheekmax.shop/# online apotheek

Betrouwbare online apotheek zonder recept Betrouwbare online apotheek zonder recept online apotheek

Kamagra Gel: Kamagra Original – Kamagra Oral Jelly

https://kamagrapotenzmittel.shop/# Kamagra Oral Jelly

Apotek hemleverans recept: apotek online – apotek online recept

https://apotheekmax.shop/# Apotheek Max

online apotheek: Online apotheek Nederland met recept – Beste online drogist

https://kamagrapotenzmittel.com/# Kamagra kaufen ohne Rezept

apotek pa nett apotek online apotek online

http://apotekonlinerecept.com/# Apoteket online

Kamagra Oral Jelly kaufen: kamagra – Kamagra Oral Jelly

apotek online recept: apotek online – Apoteket online

https://apotheekmax.com/# Beste online drogist

https://kamagrapotenzmittel.com/# Kamagra Original

ApotheekMax: ApotheekMax – Beste online drogist

http://apotekonlinerecept.com/# Apotek hemleverans recept

Kamagra Original: Kamagra Original – Kamagra Oral Jelly

Kamagra Oral Jelly kaufen Kamagra Oral Jelly kaufen Kamagra kaufen ohne Rezept

apotek online recept: apotek online recept – apotek pa nett

http://kamagrapotenzmittel.com/# Kamagra online bestellen

http://kamagrapotenzmittel.com/# Kamagra Original

https://apotheekmax.shop/# online apotheek

Online apotheek Nederland met recept: Apotheek online bestellen – Betrouwbare online apotheek zonder recept

Apoteket online: Apoteket online – apotek online recept

http://kamagrapotenzmittel.com/# kamagra

Kamagra kaufen ohne Rezept Kamagra Oral Jelly Kamagra kaufen ohne Rezept

Apoteket online: apotek pa nett – Apoteket online

http://apotekonlinerecept.com/# apotek online

https://apotekonlinerecept.shop/# Apotek hemleverans recept

Online apotheek Nederland met recept: Betrouwbare online apotheek zonder recept – Apotheek Max

Apotek hemleverans recept: Apoteket online – apotek pa nett

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

Apotek hemleverans idag Apoteket online apotek online recept

reputable indian pharmacies: indian pharmacy online – www india pharm

http://agbmexicopharm.com/# Agb Mexico Pharm

my canadian pharmacy review: canadian pharmacies – canadian pharmacy store

reliable canadian pharmacy go canada pharm canada pharmacy 24h

http://agbmexicopharm.com/# Agb Mexico Pharm

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: Agb Mexico Pharm – Agb Mexico Pharm

mexico drug stores pharmacies: Agb Mexico Pharm – mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

medicine in mexico pharmacies: Agb Mexico Pharm – reputable mexican pharmacies online

legitimate canadian online pharmacies: go canada pharm – canadian pharmacy meds reviews

http://wwwindiapharm.com/# indian pharmacies safe

canada drug pharmacy canadian pharmacy drugs online reputable canadian pharmacy

cheapest online pharmacy india: www india pharm – buy prescription drugs from india

pharmacy in canada: the canadian pharmacy – canada drugs online reviews

canadian pharmacy 24h com safe: GoCanadaPharm – canadian pharmacy victoza

www india pharm: www india pharm – indian pharmacy

Agb Mexico Pharm: pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa – Agb Mexico Pharm

world pharmacy india www india pharm best india pharmacy

www india pharm: best india pharmacy – www india pharm

medication from mexico pharmacy: buying prescription drugs in mexico – Agb Mexico Pharm

https://wwwindiapharm.com/# pharmacy website india

Agb Mexico Pharm: Agb Mexico Pharm – Agb Mexico Pharm

canadian pharmacy no rx needed: go canada pharm – canadian drugstore online

ordering drugs from canada: GoCanadaPharm – reliable canadian pharmacy

Agb Mexico Pharm purple pharmacy mexico price list Agb Mexico Pharm

canadian pharmacy world: GoCanadaPharm – best canadian pharmacy

india pharmacy mail order: world pharmacy india – www india pharm

Agb Mexico Pharm: pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa – Agb Mexico Pharm

canadian pharmacy: northwest canadian pharmacy – canadian pharmacy 24

Agb Mexico Pharm: buying from online mexican pharmacy – medication from mexico pharmacy

https://agbmexicopharm.shop/# purple pharmacy mexico price list

Agb Mexico Pharm: Agb Mexico Pharm – pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

india pharmacy mail order: top online pharmacy india – www india pharm

https://agbmexicopharm.shop/# Agb Mexico Pharm

1 lisinopril: Lisin Express – buy lisinopril 20 mg

AmOnlinePharm: amoxicillin pharmacy price – buy amoxicillin 500mg capsules uk

ZithPharmOnline: zithromax prescription in canada – ZithPharmOnline

http://predpharmnet.com/# prednisone for sale no prescription

where can i get cheap clomid without insurance: where to buy clomid prices – cheap clomid pill

amoxicillin medicine: how to get amoxicillin over the counter – where to buy amoxicillin pharmacy

Clom Fast Pharm can i buy clomid without rx where to buy generic clomid without a prescription

where to buy clomid without insurance: generic clomid prices – Clom Fast Pharm

how to buy cheap clomid price: Clom Fast Pharm – get clomid no prescription

lisinopril 10 mg daily: lisinopril 80mg tablet – lisinopril tab 100mg

Clom Fast Pharm: Clom Fast Pharm – order generic clomid

amoxicillin 500 mg online: AmOnlinePharm – AmOnlinePharm

buy 10 mg prednisone prednisone 1 tablet prednisone 50 mg for sale

5mg prednisone: Pred Pharm Net – Pred Pharm Net

zestoretic 20: lisinopril 40 mg tablet – lisinopril 10 mg over the counter

AmOnlinePharm: amoxicillin 500 mg online – how much is amoxicillin prescription

https://predpharmnet.com/# Pred Pharm Net

lisinopril cost uk Lisin Express how much is lisinopril 10 mg

prednisone rx coupon: Pred Pharm Net – Pred Pharm Net

https://predpharmnet.com/# order prednisone online canada

Lisin Express: Lisin Express – cost of prinivil

zithromax online usa: ZithPharmOnline – ZithPharmOnline

AmOnlinePharm: AmOnlinePharm – AmOnlinePharm

prednisone cost in india prednisone 20 mg tablet prednisone buying

https://lisinexpress.shop/# Lisin Express

AmOnlinePharm: AmOnlinePharm – can you buy amoxicillin over the counter

Pred Pharm Net: Pred Pharm Net – prednisone online

https://predpharmnet.com/# prednisone without rx

Pred Pharm Net: Pred Pharm Net – mail order prednisone

amoxicillin discount coupon: azithromycin amoxicillin – where to buy amoxicillin 500mg

AmOnlinePharm: where can i get amoxicillin 500 mg – amoxicillin discount

Lisin Express Lisin Express Lisin Express

http://amonlinepharm.com/# AmOnlinePharm

Lisin Express: generic lisinopril 40 mg – zestril medication

https://predpharmnet.shop/# Pred Pharm Net

generic zithromax azithromycin how to get zithromax over the counter ZithPharmOnline

ZithPharmOnline: zithromax online usa no prescription – zithromax 600 mg tablets

Pred Pharm Net: prednisone 5084 – Pred Pharm Net

zithromax online: zithromax price south africa – ZithPharmOnline

kaГ§ak bahis siteleri bonus veren: casibom giris adresi – en iyi bahis siteleri 2024 casibom1st.com

by casino: bet bahis giriЕџ – deneme bonusu veren siteler casinositeleri1st.com

guvenilir casino siteleri: casino siteleri 2025 – popГјler bahis siteleri casinositeleri1st.com

kumar oynama siteleri: casibom giris – gГјvenli siteler casibom1st.com

slot casino siteleri: canlД± oyunlar – kazino online casinositeleri1st.com

sweet bonanza oyna: sweet bonanza yorumlar – sweet bonanza slot sweetbonanza1st.shop

https://sweetbonanza1st.com/# sweet bonanza yorumlar

casino siteleri casino siteleri 2025 lisansl? casino siteleri casinositeleri1st.shop

deneme bonusu veren siteler: guvenilir casino siteleri – deneme bonusu veren siteler casinositeleri1st.com

slot casino siteleri: guvenilir casino siteleri – casino siteleri casinositeleri1st.com

slot casino siteleri: deneme bonusu veren siteler – casino siteleri casinositeleri1st.com

slot casino siteleri: casino siteleri – casino siteleri 2025 casinositeleri1st.com

tГјrkiye nin en iyi yasal bahis sitesi: casibom giris – online kumar siteleri casibom1st.com

vaycasino casibom guncel adres online casino websites casibom1st.shop

sweet bonanza giris: sweet bonanza yorumlar – sweet bonanza demo sweetbonanza1st.shop

sweet bonanza giris: sweet bonanza siteleri – sweet bonanza demo sweetbonanza1st.shop

grand pasha bet: casibom giris – gГјvenilir oyun alma siteleri casibom1st.com

deneme bonusu veren siteler: guvenilir casino siteleri – bahis giriЕџ casinositeleri1st.com

lisansl? casino siteleri: casino siteleri – en bГјyГјk bahis siteleri casinositeleri1st.com

curacao lisans siteleri: casibom mobil giris – en Г§ok freespin veren slot 2025 casibom1st.com

gore siteler casibom 1st en gГјvenilir online casino casibom1st.shop

sweet bonanza yorumlar: sweet bonanza siteleri – sweet bonanza yorumlar sweetbonanza1st.shop

casinox: casibom mobil giris – online casino websites casibom1st.com

sweet bonanza 1st: sweet bonanza giris – sweet bonanza slot sweetbonanza1st.shop

casino siteleri: deneme bonusu veren siteler – lisansl? casino siteleri casinositeleri1st.com

sweet bonanza yorumlar: sweet bonanza siteleri – sweet bonanza yorumlar sweetbonanza1st.shop

slot casino siteleri casino siteleri guvenilir casino siteleri casinositeleri1st.shop

sweet bonanza demo: sweet bonanza demo – sweet bonanza yorumlar sweetbonanza1st.shop

slot casino siteleri: casino siteleri – lisansl? casino siteleri casinositeleri1st.com

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

sweet bonanza oyna: sweet bonanza demo – sweet bonanza demo sweetbonanza1st.shop

sweet bonanza siteleri: sweet bonanza siteleri – sweet bonanza sweetbonanza1st.shop

deneme bonusu veren gГјvenilir siteler: casibom giris adresi – bonus veren yasal bahis siteleri casibom1st.com

https://casibom1st.com/# yasal kumar siteleri

guvenilir casino siteleri slot casino siteleri slot casino siteleri casinositeleri1st.shop

canlД± casino bahis siteleri: casibom giris – deneme bonusu veren yeni siteler 2025 casibom1st.com

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

casino siteleri: casino siteleri – guvenilir casino siteleri casinositeleri1st.com

sweet bonanza slot: sweet bonanza – sweet bonanza sweetbonanza1st.shop

USMexPharm: USMexPharm – USMexPharm

https://usmexpharm.com/# USMexPharm

mexican pharmacy Mexican pharmacy ship to USA mexican pharmacy

mexican pharmacy: Mexican pharmacy ship to USA – purple pharmacy mexico price list

https://usmexpharm.com/# medication from mexico pharmacy

certified Mexican pharmacy: mexican pharmaceuticals online – buying from online mexican pharmacy

mexican pharmacy: usa mexico pharmacy – UsMex Pharm

UsMex Pharm: UsMex Pharm – Mexican pharmacy ship to USA

http://usmexpharm.com/# USMexPharm

mexican pharmacy: certified Mexican pharmacy – Us Mex Pharm

mexican rx online: UsMex Pharm – USMexPharm

USMexPharm: UsMex Pharm – USMexPharm

https://usmexpharm.shop/# Us Mex Pharm

Us Mex Pharm: certified Mexican pharmacy – usa mexico pharmacy

certified Mexican pharmacy: mexican pharmaceuticals online – buying from online mexican pharmacy

mexican pharmaceuticals online mexican pharmacy mexican pharmacy

https://usmexpharm.shop/# Mexican pharmacy ship to USA

mexican pharmacy: usa mexico pharmacy – mexican pharmacy

mexico drug stores pharmacies: usa mexico pharmacy – USMexPharm

You have to make sure about what your regular ranges are (even before cycling so you could have a reference point) and you want to know what the Anabolic Steroid(s) did.

Keep In Mind, 15 ways to identify someone on steroids include adjustments

in physique and conduct. Effective PCT aims to counter these

adjustments and support a healthy recovery. Testosterone is a pure compound produced by

the Gonads in the body, however as with each single Steroid you possibly can lay your arms

on, it’ll cause downregulation of endogenous Testosterone production [1].

I’ve been using enclomiphene (or occasionally, common clomiphene)

for about 2 years now. That was close to the end of ~12 weeks of using RAD-140 which I

anticipated would have suppressed me a bit more despite the use of enclomiphene.

I’m not sure of the mechanism by which anavar impacts the HTPA, but

even when it did apparently I have a bit of room to spare.

There are additionally blood stress kits you should buy online,

enabling you to watch your levels even more incessantly.

This oral steroid is a Dihydrotestosterone (DHT) derivative hormone

that has been structurally altered. The recommended dosage of Anvarol

is three capsules per day, taken with water roughly quarter-hour after your

workout.

Most of these will solely be of concern if you’re utilizing doses that are too excessive or

utilizing the drug for longer than recommended intervals.

As expected, most reviews and experiences from actual individuals using Anavar are constructive.

Folks report wonderful results for weight loss, chopping, and preserving muscle tissue, which is the place Anavar excels.

Most male competitors will have between 3% and 5% physique fat throughout competitions.

Remember that these are essentially the most extreme users, and they’re probably to make use of

different compounds alongside or as a substitute

of Anavar. Anavar can contribute somewhat to some lean features, however for male users, it’s

most unlikely to be a reason for utilizing this steroid. Instead, the anabolic properties of Anavar are most dear for men in phrases

of MAINTAINING muscle when dropping fat.

Underground labs refer to manufacturing facilities that aren’t

legally permitted and haven’t any regulation or oversight of

their practices. These labs can be something from professional-type amenities to a

makeshift basement lab. You won’t understand how

or where your Testosterone Enanthate is being manufactured in underground labs

or precisely what’s been put into it. This runs the danger of purchasing products

of poor high quality and doubtlessly even harmful Testosterone Enanthate if well being and safety measures haven’t been adhered

to. You know you’re getting one of the best model if you’ll

find Testosterone Enanthate at a pharmaceutical grade stage.

The finest pharmaceutical-grade Testosterone Enanthate can additionally be expected to be the most expensive.

When it involves acne, some users will develop extreme pimples, however other guys find they have

very little drawback with their pores and skin.

Users’ genetic make-up will decide the extent of hair loss they will experience.

Anavar is a DHT-derived steroid; thus, accelerated hair loss can be skilled in genetically prone individuals.

Nonetheless, Anavar is unique on this respect, being mostly metabolized by the kidneys.

Dr. Jack Parker, holding a Ph.D. and pushed by a deep

ardour for health, is a trusted expert in bodily

well being and authorized steroids. He blends thorough

analysis with hands-on expertise to help Muzcle readers achieve their fitness objectives safely and effectively.

Exterior of work, Jack loves spending time with his family and maintaining with the newest health

tendencies and research. Anavar, identified

generically as Oxandrolone, is praised for its comparatively mild impression and

versatility. When it comes to Anavar dosage, much less can typically be more because of its mild nature

and a lower incidence of unwanted facet effects in comparability with

different anabolic steroids.

It is much safer and simpler to select other choices if you wish to boost your athletic efficiency, retain your muscle mass or

just enhance your energy ranges. SERMs like Nolvadex (Tamoxifen Citrate) and Clomid (Clomiphene) are incredibly frequent in a

post cycle therapy protocol and are medically used to treat breast

cancer. All Anabolic steroids will cause downregulation of both LH and FSH ranges, which in turn will cease the Leydig cells from producing Testosterone

[2]. For occasion, if you’re interested by is

Cbum pure or is David Laid natural, it’s all about understanding how

these cycles influence your body and managing those effects.

100mg of testosterone enanthate weekly for 12 weeks is

sufficient to help the conventional function of the hormone.

By limiting testosterone in this cycle, Anavar is

left to take on the first anabolic function, bringing about lean positive

aspects and unimaginable fat loss and toning throughout the cycle.

Though Anavar is not the most potent anabolic steroid, it still has a notable effect

on lean muscle mass. In scientific settings, even sedentary males

have skilled positive modifications.

These compounds offer unique benefits and downsides, so it’s essential to analysis

and understand how they could align together with your objectives.

Whereas Anavar’s side effects could seem much less dramatic, they should not be missed.

Prevention, as with many things, could be far more value effective than the remedy — both by way

of health and efficiency. By combining Testosterone and Anavar, customers purpose to see synergistic results that yield results greater than what could

be achieved through the use of either compound alone.

Post-cycle therapy (PCT) is a vital side of any steroid cycle, including the mix of Masteron and Take A Look At.

It aims to restore natural hormone manufacturing, decrease unwanted effects, and preserve the positive aspects achieved

in the course of the cycle. After finishing a

cycle of the dietary supplements, the body’s natural hormone production could also be suppressed.

PCT helps to kick-start this manufacturing, allowing the body to regain its hormonal stability.

Furthermore, it mitigates the chance of potential unwanted side effects, corresponding to estrogen-related issues, by regulating hormone

ranges. Usually, it ought to start as soon as exogenous steroid levels have significantly decreased in the physique.

A common method is to initiate PCT round 1-2 weeks after the last steroid administration.

In all but essentially the most excessive circumstances, girls wanting to realize maximum leanness will concentrate on getting to

10%-15% body fat. But Anavar isn’t simply nice for fat loss for ladies, however even more so for sustainable and aesthetically pleasing lean features

with no or minimal unwanted side effects. Males

on a cutting cycle with Anavar can count on a superb fats loss,

and will in all probability be quite quick as a

outcome of Anavar is a quick-acting steroid that

you’ll only use for eight weeks max. Using Anavar at

low to moderate doses is about as secure as it could possibly get for

anabolic steroid use. As with many other compounds, it is unknown for its severe unwanted effects.

However abuse Anavar past the really helpful utilization patterns, and also you do set yourself up for an unsafe steroid expertise that can and can harm your health.

Exceptional fat loss shall be seen on this stack, and it will come on shortly.

Anavar can also be very costly, so if you’re looking for an inexpensive Dianabol stack, this is in all

probability not for you. Liver toxicity might be notable solely because of Dianabol; trenbolone will

not improve hepatic strain. Trenbolone is extraordinarily androgenic, with a ranking of

500, roughly 10 instances that of Dianabol.

Dr. John Ziegler was entrusted with growing a steroid that was stronger than testosterone so as

to assist the US Olympic team in defeating the Soviets within the Nineteen Fifties.

References:

d Ball steroid Results (Cdeexposervicios.com)

Mexican pharmacy ship to USA: UsMex Pharm – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

https://usmexpharm.com/# USMexPharm

mexican pharmacy: mexico pharmacies prescription drugs – UsMex Pharm

USMexPharm: mexican pharmacy – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

certified Mexican pharmacy: usa mexico pharmacy – certified Mexican pharmacy

Mexican pharmacy ship to USA: usa mexico pharmacy – USMexPharm

https://usmexpharm.com/# usa mexico pharmacy

Us Mex Pharm: Us Mex Pharm – buying prescription drugs in mexico online

Mexican pharmacy ship to USA mexican pharmacy USMexPharm

https://usaindiapharm.com/# UsaIndiaPharm

UsaIndiaPharm: USA India Pharm – UsaIndiaPharm

UsaIndiaPharm: Online medicine home delivery – UsaIndiaPharm

UsaIndiaPharm: indianpharmacy com – UsaIndiaPharm

http://usaindiapharm.com/# USA India Pharm

п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india: UsaIndiaPharm – reputable indian pharmacies

USA India Pharm: top online pharmacy india – indian pharmacy paypal

indian pharmacies safe USA India Pharm UsaIndiaPharm

Online medicine order: Online medicine order – reputable indian pharmacies

http://usaindiapharm.com/# reputable indian online pharmacy

USA India Pharm: USA India Pharm – UsaIndiaPharm

india pharmacy mail order: top online pharmacy india – UsaIndiaPharm

india online pharmacy: india pharmacy mail order – UsaIndiaPharm

indian pharmacy online: top 10 pharmacies in india – USA India Pharm

https://usaindiapharm.com/# Online medicine order

online shopping pharmacy india: UsaIndiaPharm – buy prescription drugs from india

UsaIndiaPharm: buy medicines online in india – Online medicine order

indian pharmacy: USA India Pharm – best india pharmacy

https://usaindiapharm.com/# indian pharmacy online

UsaIndiaPharm: USA India Pharm – п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

UsaIndiaPharm: world pharmacy india – USA India Pharm

USA India Pharm: pharmacy website india – buy medicines online in india

https://usaindiapharm.shop/# USA India Pharm

USA India Pharm: reputable indian pharmacies – USA India Pharm

pharmacy website india: india pharmacy – UsaIndiaPharm

reputable indian online pharmacy: buy prescription drugs from india – USA India Pharm

http://usaindiapharm.com/# п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

UsaIndiaPharm: online shopping pharmacy india – UsaIndiaPharm

UsaIndiaPharm: reputable indian pharmacies – reputable indian online pharmacy

UsaIndiaPharm online pharmacy india USA India Pharm

mail order pharmacy india: online shopping pharmacy india – UsaIndiaPharm

UsaIndiaPharm: best india pharmacy – UsaIndiaPharm

http://usaindiapharm.com/# USA India Pharm

UsaIndiaPharm: UsaIndiaPharm – UsaIndiaPharm

USA India Pharm: top 10 online pharmacy in india – USA India Pharm

USA India Pharm: USA India Pharm – USA India Pharm

top online pharmacy india indian pharmacy india pharmacy mail order

http://usaindiapharm.com/# USA India Pharm

UsaIndiaPharm: п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india – india online pharmacy

USA India Pharm: top 10 pharmacies in india – UsaIndiaPharm

UsaIndiaPharm: USA India Pharm – reputable indian pharmacies

http://usaindiapharm.com/# п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

india online pharmacy: online shopping pharmacy india – indian pharmacy paypal

UsaIndiaPharm: USA India Pharm – USA India Pharm

indian pharmacy UsaIndiaPharm USA India Pharm

USA India Pharm: UsaIndiaPharm – cheapest online pharmacy india

https://usaindiapharm.com/# indianpharmacy com

top 10 pharmacies in india: UsaIndiaPharm – USA India Pharm

top 10 pharmacies in india: buy prescription drugs from india – online shopping pharmacy india

Although the results are not as highly effective as precise Anavar, they come with

no side-effects or well being dangers, which is why they’re gaining

popularity than ever earlier than. Moreover, Anavar has additionally been proven in some research to be effective at treating anemia

and growing levels of hemoglobin or red blood cells. It might have a optimistic impact on HDL

cholesterol (the “good” kind) and whole cholesterol for people with

high triglyceride levels. Anavar can even improve bone density,

which can assist to reduce the danger of osteoporosis.

There is a product known as Anvarol which is a real various that

is made up of all-natural ingredients. From my own private experience,

most girls want something that will burn fats and give

them exhausting and toned muscle. Many labs promote Anavar in doses as little as 2.5 mg but a number of the extra

widespread doses are out there in presentations 10,

20 and 50mg oral drugs which is an excessive quantity of for women. This makes perfect

senses, during a chopping cycle most women cut back on energy

and carbs which can cut back power ranges.

Anadrol is considered one of the most potent bulking steroids, producing slightly extra weight accumulation than Dianabol.

Anavar will end in an imbalance in HDL and LDL ranges, which will have an result on a user’s ldl cholesterol profile.

Although Anavar is much less cardiotoxic compared to

most anabolic steroids, it nonetheless has the potential to induce hypertension.

Its bone-protective effects make it a promising adjunct treatment in osteoporosis administration, reinforcing its purposes past muscle-building (Johannsson, Medical Endocrinology).

This article explores Anavar’s role in a steroid cycle, its unique benefits,

really helpful utilization, and key concerns

for maximizing its effectiveness while minimizing risks.

You may assume that a big boost in libido and bedroom exercise may be a

great factor to be reporting. However overuse of anabolic steroids can cause a

painful or extended erection [10]. And that’s additionally definitely not a good factor to happen whenever

you’re trying to focus on your squats or standing in a queue at Starbucks.

I can relate to the slight lack of energy and darkend urine and a slight little bit of joint pain but aside

from that no real problems. For the male athlete in his bulking season the Oxandrolone hormone is usually reasoned to be a poor

alternative as it’s not well-suited for big buildups in mass.

Make no mistake; it can build lean tissue just not

to any important degree. For bodybuilders, there is the

will to look fit with out exposing themselves to well being implications and different risks like severe medicine unwanted effects.

This naturally evokes the search for a more effective different to artificial steroids.

The active ingredient on this drug is Oxandrolone, which is used in medication to help people who are unable to realize or maintain proper weight for medical causes.

Users usually report feeling an energy boost, improved strength and endurance

in the gym, and better muscle pumps. Nonetheless, unwanted side effects may embrace increased aggression, insomnia, complications and lack of urge for food.

Nonetheless, the danger of severe liver issues and the fact that Anavar is meant only for short-term use

argues towards its security as a bodybuilding

or performance-enhancing drug. Nonetheless, it’s essential to weigh

these advantages towards the potential dangers. Anavar

can impact liver well being and levels of cholesterol, and its use requires careful monitoring and adherence to beneficial dosages.

Post-cycle therapy is essential to revive natural hormone ranges and maintain the positive aspects achieved through the cycle.

Understanding these elements and being ready to handle them

is key to a profitable expertise with Anavar.

Anavar and Winstrol possess many similarities, with each decreasing fats mass and water retention while growing lean muscle mass.

Anavar doesn’t aromatize to estrogen, meaning it does not convert to estradiol.

Moreover, it’s not a substrate for 5α-reductase, so it isn’t converted into dihydrotestosterone (DHT), which contributes to points like

hair loss and prostate enlargement in males. Managing this requires good biking, monitoring, and doubtlessly integrating estrogen administration methods.

In this cycle sample, the Anavar dose of 20 mg/day is maintained for eight weeks.

This dose is usually adopted by people who’ve previously taken Anavar or different

anabolic steroids. Always use Anavar under a doctor’s steerage, and by no means exceed the beneficial dosage.

Regularly monitor your health, particularly your liver perform and cholesterol levels.

Females working a primary Anavar cycle ought to begin very low

to judge side effects. 5mg per day is known to be well tolerated in clinical use by many female patients.

If a lady tolerates this dose properly, the subsequent step is 10mg; many will find 10mg daily to be

the perfect steadiness. Nevertheless, various ladies confidently use 15 and even 20mg every

day, which is ready to enormously enhance the chance of virilizing side effects.

The different critical issue when dosing Anavar is whether or not you’re stacking it with

different AAS at efficiency doses and simply how strong of a job

you need Anavar to play in the cycle. Most males won’t

use Anavar as a sole compound because of its weaker effects, but it’s widespread for women to

run Anavar-only cycles. At probably the most basic level, you’ll

have the ability to expect to see some good fat loss and a few moderate muscle

features if you use Anavar.

What it does do, is help to burn visceral fats and promote features in lean muscle tissue.

Furthermore, in phrases of advantages, Winstrol will supply some benefits compared to Anavar.

It has a greater drying effect, probably because of the truth that

winstrol lowers Progesterone which may decrease water retention. The

really helpful Anavar dosage for athletes usually ranges from 20mg

to 80mg per day. This dosage could be split into two to 4 doses

per day, relying on the individual’s tolerance and expertise degree.

References:

steroid freak

buy prescription drugs from india: cheapest online pharmacy india – best india pharmacy

canadian pharmacy: canadian drugs pharmacy – USACanadaPharm

http://usacanadapharm.com/# real canadian pharmacy

canadian pharmacy online ship to usa: usa canada pharm – usa canada pharm

usa canada pharm: canadian pharmacy online – canadian pharmacy world

usa canada pharm canadian pharmacy ltd usa canada pharm

USACanadaPharm: canadian pharmacy reviews – USACanadaPharm

https://usacanadapharm.com/# canadian pharmacy ed medications

pharmacy com canada: precription drugs from canada – canadian online pharmacy

canadian pharmacy cheap: legal to buy prescription drugs from canada – canadian pharmacy cheap

legit canadian pharmacy: usa canada pharm – usa canada pharm

http://usacanadapharm.com/# USACanadaPharm

USACanadaPharm: reputable canadian pharmacy – canadian pharmacy online store

usa canada pharm: onlinepharmaciescanada com – usa canada pharm

usa canada pharm: USACanadaPharm – usa canada pharm

http://usacanadapharm.com/# pharmacies in canada that ship to the us

USACanadaPharm legitimate canadian pharmacy online precription drugs from canada

USACanadaPharm: USACanadaPharm – onlinecanadianpharmacy

http://usacanadapharm.com/# USACanadaPharm

online canadian pharmacy: usa canada pharm – legit canadian pharmacy

However, clenbuterol is not an anabolic steroid; subsequently, we

don’t see it have an result on pure testosterone ranges

to any significant diploma. There is a common notion that girls don’t require post-cycle

therapy. Nevertheless, in apply, we find ladies experience multiple signs of clinically low testosterone levels following anabolic steroid use.

Beforehand, we cited a research that said men taking 20 mg a day for 12 weeks skilled

a 45% decrease in testosterone ranges. This was an extreme cycle duration,

with a standard cycle length of 6–8 weeks for men. From this examine,

we will conclude that natural testosterone production is more probably to stay fairly excessive if a reasonable dose or cycle is carried out.

As A Result Of we’re using steroids for performance enhancement

and bodybuilding, the compounds are being taken at doses a

lot greater than in the event that they have been used for medical functions.

The larger your dosage, the greater your danger of antagonistic

well being effects. Trenbolone is a extremely potent chopping agent that is identified for its

capacity to increase muscle mass whereas promoting fats loss.

When stacked with Anavar, it could help to amplify the muscle-building and fat-burning effects of

each compounds.

If you need to get the most effective outcomes whereas slicing, you have to create a calorie shortfall.

It’s regular to gain fat in addition to muscle and to build more muscle

tissue. The quantity of fat achieve can be notably unhealthy when you use a method known as

soiled bulking. Testosterone is also an essential pure steroid that plays a key role in protein synthesis

and helps your muscles to grow. A testosterone cycle helps the fat-burning course of as properly and does many different things apart

from.

CrazyBulk is also providing a buy-two-get-one-free deal on all of their merchandise in the meanwhile,

so it’s a nice time to start your bulking or slicing

cycle. The conclusion about an Anavar cycle is that it is a successful way to lose weight.

In fact, if accomplished appropriately, many individuals discover they’ll maintain the load off for fairly a while.

Nevertheless, there are some belongings you need to listen to when doing this sort

of cycle. First and foremost, you want to ensure you

are taking enough calories through the day so that you

just don’t feel hungry.

It’s also sensible to steer clear of high-fat diets that can additional disrupt cholesterol levels.

Lastly, keep away from prolonged use to attenuate

the chance of long-term injury to your body. Whereas it is extremely

well-tolerated indicators of virilization can occur however they’re uncommon and extremely

rare if the lady plans her Anavar cycle in a accountable method.

Anavar, also called Oxandrolone, is an oral AAS that’s extensively

considered to be one of the safest and mildest steroids in the

marketplace. It was originally developed for medical purposes,

corresponding to treating muscle losing, however is now primarily used for bodybuilding and athletic

efficiency enhancement. This stack is very androgenic, so

there will be considerable fats loss in addition to prominent strength and muscle positive

aspects. It doesn’t matter when you have been bulking or

cutting, when you have been utilizing anabolic steroids, the need

is all the time there.

As A Outcome Of Anavar helps to burn fats and Winstrol

is extra anabolic, so not solely can you lose more physique fats, you’ll also

probably build extra muscle than when you used both

alone. Results can sometimes be seen inside two weeks of consistent use coupled with the appropriate food regimen and exercise regimen. Nevertheless, individual results may differ depending on several circumstances, like body

composition, diet, workout depth, and the user’s specific targets.

It is essential to notice that outcomes ought to be measured in phrases of enhancement in power and discount

in body fats, not solely weight reduction. The multifaceted features of

Anavar, whether or not used for chopping or as a software for weight loss, exhibit a

priceless attraction to the health group.

Moreover, using Anavar solely for bulking purposes might not give essential results; thus it’s wise to hitch it with other steroids like Winstrol.

Moreover, post-cycle remedy (PCT) is necessary after discontinuing

the drug to help restore natural testosterone production ranges.

Did you know Anavar was first created in 1964 by pharmaceutical firm Searle Laboratories?

Stacking a small quantity of Testosterone (150mg – 300mg per week)

with Var and Tbol would make for a light yet effective

lean bulk or recomping cycle. Dosing Anavar at 40mg and Turinabol also at 40mg for

not than four to six weeks would offer sufficient anabolism with out overdoing it the place opposed unwanted side effects are concerned.

Yet, whereas the load loss advantages are substantial, testimonials spotlight the importance of implementing a caloric

deficit and sustaining a health-conscious food regimen for maximizing

results. The drug isn’t a magic weight-loss pill, but with correct coaching and food

regimen strategies, it could foster substantial transformation. Persistence, endurance,

and discipline, accompanied by the drug’s fat-burning and muscle-preserving attributes, have led numerous customers to a extra compelling health and fitness story.

An eight-week Anavar cycle can function a substantial milestone for users, permitting them to grasp the drug’s potential effects on their our bodies.

We have discovered aromatase inhibitors to be

ineffective at stopping gynecomastia from Anadrol, because it doesn’t convert testosterone to estrogen. Thus, it’s

hardly ever run, typically and typically solely by experienced steroid users.

We have seen bodybuilders efficiently cycle the 2 together just before a contest, trying lean, dry, and full.

The trick is to consume low amounts of sodium, which prevents the bloating effect that Anadrol

can cause.

References:

What Are Steroids Good For (C-Hireepersonnel.Com)

With every pill exactly dosed at 10mg, supplementation turns into a breeze.

Say goodbye to advanced injections or powders—ANAVAR10 lets you focus in your goals with out

distractions. Unfortunately, Primobolan is probably probably

the most faked steroid being sold in UGL labs right now.

Deca is a great addition and can noticeably enhance your joint function and total restoration. Anavar will improve and

build upon all the consequences of Primo and have you getting extra ripped than is possible with Primo alone.

If you select to take Anavar earlier than your workout, it’s usually

really helpful to take action approximately 30 to 60 minutes beforehand.

This allows sufficient time for the compound to be absorbed and exert its results by the point you start your coaching session. In The

End, the best time to take Anavar might vary from individual to individual.

Components such as your particular person targets, schedule, and response to the drug can influence the optimal timing for you.

It is important to take heed to your physique and experiment with different timing strategies to discover out what works greatest for

you.

Given that correctly dosing anabolic steroids is crucial to the prevalence of each constructive and negative effects,

it’s imperative to take somewhat time to figure out which dosage(s) would possibly work finest

for you. Potential liver toxicity is at all times a concern, significantly

when utilizing oral steroids. Still, Primobolan comes with the advantage

of not posing a threat to the liver, as there

are not any known instances of liver hepatotoxicity reported for

this steroid. Nonetheless, since most people will stack Primobolan with

other steroids that will themselves cause hepatotoxicity,

it’s important to remember of the dangers to the liver of every compound you’re taking.

This is only an issue for men; female users won’t be affected by testosterone suppression when utilizing

Primobolan.

Enhanced protein synthesis can also assist in recovering and preserving current muscle tissue.

On a fats loss or cutting cycle where you eat less, losing muscle is a real threat.

To keep your muscle mass, you need the protein stability to remain at

zero; if it falls under this, your muscle gets damaged down.

So, increased protein synthesis helps construct NEW muscle and helps you keep

the lean positive aspects you’ve worked onerous for.

When cycled together, fats loss, muscle gains, and energy shall be enhanced (as against working a Winstrol-only cycle).

Anadrol is very estrogenic, so biking this steroid at

the aspect of a high-sodium food regimen is a recipe for water retention and smooth muscles.

When Winstrol is stacked with testosterone, energy

and muscle gains shall be enhanced. However, because of some doubtless water retention from

the addition of testosterone, it’s more appropriate for bulking.

Though Winstrol just isn’t commonly used as a primary steroid cycle due to its tendency

to trigger harsh side effects, the following protocol on rare

occasions has been taken by beginners (utilizing lower doses).

One of Winstrol’s most regarding unwanted effects is its influence on heart well being,

particularly the method it skews your cholesterol levels

to favor dangerous cholesterol while decreasing good ldl

cholesterol. This can negatively affect your coronary heart when you

permit its cholesterol-raising results unchecked.

However that’s just one facet of the story… Efficiency doses take issues to a new stage because we want to profit from Anavar’s anabolic effects past what’s required in medical therapies.

How a lot physique fats can be lost depends on your present physique

composition; Anavar shouldn’t be considered a magic weight

loss tablet. Anavar’s precise worth exists the place you’re already lean and where Anavar’s hardening and drying physique can showcase

those previous few percentages of fat you’ve

shed.

You might help to counter this impact by sustaining a cholesterol-friendly

diet that’s high in omega-3 fatty acids and low in saturated

fats and easy carbohydrates. Even if you’re cutting…providing you’re coaching hard,

consuming proper, and utilizing other powerful steroids alongside primo,

it’s really possible to construct a noticeable amount of muscle on Primobolan.

As you’d count on, the quantity of every steroid you take and how lengthy you employ it’s going to primarily affect its detection time.

With greater doses, your metabolism works to break down more of the steroid at its natural price of metabolism.

Larger doses can outcome in slower hormone metabolism as the physique

works harder with its obtainable enzymes and other substances

concerned in the metabolic course of.

So much so that it has been used successfully and with out issues in children and untimely infants to advertise weight acquire.

Step on the human development hormone gasoline, fire up muscle progress and burn through fat stores.

Anavar can also impact levels of cholesterol, reducing HDL (good) ldl cholesterol and growing LDL (bad) cholesterol.

One of the the cause why Anavar is so in style is because it’s a comparatively secure steroid.

It has a low risk of causing liver damage,

and it doesn’t aromatize (convert to estrogen) within the physique, which implies that customers don’t have to

fret about creating gynecomastia (male breast tissue).

We have discovered Anavar’s hepatic results

to be gentle because of the kidneys working

to course of Oxandrolone, taking stress off the liver.

Equally, Testosterone Undecanoate poses little hepatic risk, bypassing the liver and being absorbed by the

lymphatic system. Many orals stimulate hepatic lipase,

an enzyme current within the liver that lowers HDL cholesterol.

Oral steroids (pills) are very handy to take;

customers simply swallow a pill with water. We discover many beginners are reluctant to utilize injectable steroids due

to a fear of needles, injecting incorrectly,

or simply being inconvenient. A descriptive study of antagonistic occasions from clenbuterol misuse and abuse for weight loss

and bodybuilding. Anavar’s testosterone-suppressing results,

nonetheless, can linger for several months.

To attempt to maintain blood strain as little as potential,

users are recommended to take four grams of fish oil per

day, mixed with clear consuming and common cardiovascular exercise.

Though cardio could also be the final thing a bodybuilder needs to do when bulking, it’ll provide cardiac safety.

Testosterone’s androgenic effects can complement the fat-burning effects of Anavar,

albeit with some temporary water retention. The biggest concern we see with

the addition of trenbolone is a spike in blood stress.

Anavar produces nice outcomes, notably by method of energy and pumps.

Take 3+ grams of fish oil and do your cardio, and cholesterol shouldn’t be a

problem, even if you’re delicate to your lipids. They are also not very hepatotoxic, which means they can be utilized for longer durations at a time.

HCG isn’t recommended for women as a PCT because of it probably enlarging ovaries (26) and causing virilization (27).

Clomid can additionally be not a positive PCT for ladies, as it may cause the ovaries to turn into oversensitive.

References:

anabolic steroid sales (careers.Zigtrading.co.za)

A 1-month Anavar cycle is normally a sensible selection for women bodybuilders who

need to experience the benefits of this steroid on a barely compressed timeline.

While the more prolonged cycles provide a broader scope for

transformation, noticeable changes can still be realized throughout a 1-month cycle.

Correct dosage recommendations are vital when it comes to using Anavar, contemplating its potent nature.

For female bodybuilders who are new to Anavar, a beginning

dosage might range from 5mg to 10mg per day, extending over a duration of 4

to six weeks.

These are two of the most efficacious bulking

steroids mixed in one cycle. Nonetheless,

if a lady has already had liver harm or consumes lots of alcohol,

she should avoid using Anavar (and different steroids) fully.

When a woman takes Anavar, her cholesterol levels may fluctuate,

with the good cholesterol (HDL) lowering and the bad cholesterol (LDL) sometimes growing.

As A End Result Of Dianabol considerably will increase the likelihood of virilization, it is a drawback for ladies.

Anavar, unlike most different anabolic steroids, isn’t a DHT-based steroid that causes testosterone to rapidly aromatize into estrogen. Anavar, then again,

is a 17-alpha alkylated anabolic steroid with decrease estrogenic and androgenic properties than DHT.

The most significant distinction between Anavar and

different steroids is its ability that will assist you lose fat without causing a significant change

in physique composition. Ultimately, every individual’s health and well-being are of paramount importance.

When contemplating adding any substance to their arsenal in the quest

for a match and sculpted physique, the potential dangers ought to

be weighed fastidiously against the benefits. Oxandrolone

can undeniably yield noticeable changes, however taking the time to gauge if these changes are price it might

potentially save plenty of future trouble. Being aware, staying

knowledgeable, and contemplating all elements are the important

steps in reaching health objectives whereas preserving well being.

Thus, we’ve seen clenbuterol improve muscular endurance, enabling bodybuilders to carry out more repetitions than usual.

Clenbuterol will increase adrenaline levels, thus shifting the body into fight-or-flight mode.

Consequently, blood flow improves all through the

body as a survival mechanism. Anavar helps flush out extracellular water making you look dry and pumped up on a daily basis.

However, if you cease taking Anavar, your muscles won’t look as dry and pumped up.

One of the best and surest ways to get all Anavar outcomes without fearing unwanted effects is by using a pure and

authorized steroid various similar to ACut from Brutal Drive.

One particular substance that has captivated my attention is Anavar, also called Oxandrolone.

However bear in mind, health journeys are like fascinating tales, they

usually unfold uniquely for each individual. Results can vary based on elements

similar to genetics, food plan, training regimen, and dosage.

It Is crucial to method Anavar with responsibility, adhere to really helpful pointers,

and seek skilled advice to make sure a safe

and efficient journey. Of course, these outcomes depend upon the individual’s

diet, train routine, dosage, and genetics. I really have discovered that many individuals report noticeable progress

after just two weeks of utilizing Anavar.

They point out increased strength and power levels, which assist them of their

exercises.

The earlier than and after photos beneath demonstrate typical

gains from a first steroid cycle. Such unwanted aspect effects, relating to

liver and cardiovascular toxicity, align with what we have

noticed from analyzing the labs of two,000 SARM customers over a 10-year interval.

Consequently, Dr. Thomas O’Connor is now of the opinion that SARMs

are extra deleterious than steroids. The more alarming unwanted effects are rare, but paying consideration to any uncommon changes is crucial.

If anything out of the ordinary occurs, it’s greatest to stop utilizing

the tablets immediately and reach out for medical help.

Lastly, it’s price noting that stacking isn’t for everyone,

and it’s usually recommended for people who have

prior expertise with steroid use. With cautious consideration and the best approach, stacking Anavar with different

steroids may be beneficial to achieving bodybuilding objectives while minimizing risks.

For those considering future Anavar cycles, it’s advisable to schedule breaks between cycles to allow your body to normalize and recover.

Breaks are crucial for minimizing potential unwanted facet effects and stopping extreme pressure on your body.

A vital issue is the gentler nature of this anabolic steroid, making it much less prone

to induce extreme side effects. The toned-down risks

provide health enthusiasts with peace of mind,

not having to worry excessively concerning the potential undesirable well

being consequences. After a accomplished cycle,

one is more probably to see a significant change in muscle definition and quality.

The muscle tissue will have a harder, denser look and

sharp definition, giving the physique a extra sculpted appearance.

This is a result of Anavar’s known property of selling

fats loss and improving muscle retention. These trajectories of transformation make the halfway

level of an Anavar cycle a moment of significant milestones and motivation.

The inherent properties in Anvarol also play an important function in firming your

muscles. Anavar stacks properly with virtually something, but I’ve discovered it to

be better with dieting. The great factor about it in addition to

giving me a tough and defined look, is it helps me stay

stronger on a caloric restriction. Anavar (Oxandrolone)

is the most properly liked steroid available on the market proper now, so

naturally I get lots of questions on it. Thus, men could be

prescribed it if they have an endogenous testosterone deficiency.

It isn’t as generally used in comparison with injectable testosterone esters as

a end result of its high price and low biological availability.

Customers may find injections less troublesome in the event that they rotate the muscular tissues they inject into.

Anabolic pro stack by high legal steroids review, anabolic

pro stack by prime legal steroids & muscle stacks. Loopy bulk authorized

steroids are the favored name amongst newbies and skilled, anavar before and after.

It in the end increases energy and power by accessing hidden testosterone cells inside the physique.

Popularly utilized by many celebrities to extend weight loss,

Anavar is a superb dietary supplement that you can add onto your stack,

anavar earlier than and after photographs.

References:

long term effects of steroids on the body

As with many different compounds, it’s unknown for its extreme

unwanted effects. However abuse Anavar beyond the beneficial utilization patterns, and also

you do set your self up for an unsafe steroid experience that can and

will harm your health. Remarkable fats loss will be seen on this stack, and it’ll come on quickly.

Count On an increase in energy and endurance, but

the unwanted effects of Clen can harm your train ability (lowering the dose

is right if you’re sensitive to stimulants).

Anavar will present the capability to construct muscle and preserve strength whereas weight-reduction plan.

As neither aromatizes to estrogen, it might be clever to add in Testosterone at artwork dose

(150mg/week) or above; in any other case, you might expertise low estrogen sides.

Anavar, on the opposite hand, is an anabolic steroid that

is often used to promote muscle progress and improve

athletic efficiency. It is also identified for its capacity to assist burn fat and enhance muscle definition. When it comes to stacking Clen and Anavar,

many individuals believe that combining these

two compounds can result in even larger fat loss and muscle

features. However, it is necessary to notice that both Clen and Anavar can have side effects, and mixing

them can increase the risk of opposed reactions. Using anabolic steroids similar to Check and Anavar can lead to vital gains in muscle

mass and energy, in addition to improved athletic

efficiency. However, you will need to weigh the potential

benefits towards the risks and unwanted aspect effects,

especially when compared to testosterone substitute therapy.

In the case of children, the total day by day dosage of Oxandrin (oxandrolone) mustn’t exceed ≤

0.1 mg per kilogram of physique weight or ≤ zero.045

mg per pound of physique weight. This will help make certain that you’re in good shape on your cycle and that you’ll see the best outcomes.

When you’re first starting out, it is necessary to cycle between the 2 steroids to see

which one works best for you. When used accurately, you possibly

can anticipate to see vital positive aspects in both energy and measurement.

By doing so, you’ll reduce your threat of unwanted effects and maximize

your outcomes.

In addition to energy gains, Anavar has been linked to increased endurance and

faster recovery times, making it a popular choice among athletes seeking

to enhance their bodily abilities. Anavar is nicely

often identified as the only anabolic steroid

women can use with little to no threat of unwanted side effects –

so lengthy as doses don’t exceed 20mg per day. Nonetheless, another compounds are additionally used by females, together with Winstrol

and Primobolan, as well as the fat-burning compound Clenbuterol.

When Anavar is used at dosages that meet the needs of bodybuilders, it does lead to suppression of the HPTA

(Hypothalamic Pituitary Testicular Axis), bringing about testosterone manufacturing suppression.

When the dosages are properly managed, I’ve noticed significant muscle gains and fast

fat loss. It’s been notably beneficial for attaining that desired dry and chiseled appearance.

After finishing my cycle, I typically wait every week earlier

than beginning PCT to assist my body’s natural hormone

production bounce again, lowering the risk of hormonal imbalances

or potential long-term damage. Be cautious to not exceed the beneficial

dosages, as this will likely increase the risk of unwanted

aspect effects.

If you want to shred body fats rapidly, safely, and effectively, then an Anavar and Clen cycle may be the right selection.

When mixed collectively, these two drugs may help you obtain your health objectives in report time.

One Other product is designed to have zero

unwanted effects whereas serving to you improve muscle gains, muscle strength, and fat loss.

This will not only help with fats loss but might help you keep muscle mass

with zero side effects. Earlier Than we proceed – know that we at

MaxHealthLiving will never endorse the use of steroids in any means.

First, it’s essential to note that Anavar and Clen are synthetic anabolic steroids, which implies that they will

have dangerous unwanted aspect effects, regardless of their gentle nature.

Primobolan can lead to reasonable muscle positive aspects and performance enhancement,

particularly in energy and endurance.

The key to a successful Winstrol and Anavar

cycle is finding the right dosage and period for my

particular body type and goals. By beginning with

a lower dose and considering changes based on my progress, I can achieve

the nice results I’m seeking with out compromising my

long-term health. I think I’m going to hold off on the NPP and just do test and anavar cycle for 12 weeks.

A beginner cycle of 500mg/week of Testosterone Cypionate for as a lot as sixteen or even 20 weeks provides excellent outcomes and minimal or no